Several researchers have tried to make this case, often relying on studies with poor measures of social media use, such as those asking if someone uses social media every day – nearly everyone who uses social media now uses it every day. We also know from studies with better measures (like those asking about hours a day of social media use) that it’s social media use of hours and hours a day that’s linked to depression, not use under an hour a day.

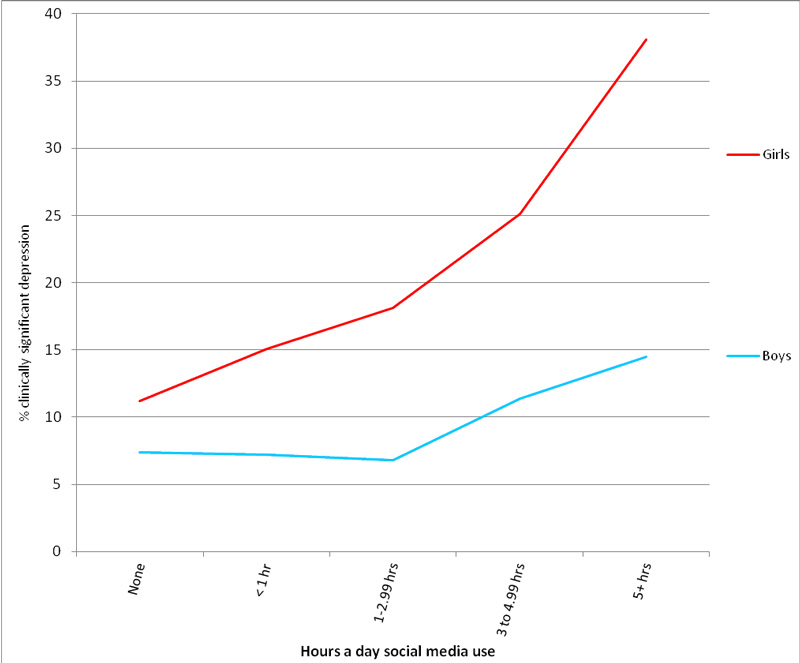

The paper most often cited to support this idea of small effects, published in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour by researchers from Oxford University, actually examined screen time overall, not social media specifically. It included watching TV, talking on the phone, and simply owning a computer as screen time, which obscured the results for social media. The same month this paper was published, another research group in the UK found that girls who spent 5 or more hours a day on social media were three times more likely to be depressed than those who did not use social media – in one of the same datasets the Oxford researchers used (see below).

In 2022, a group of Spanish researchers also concluded that the Oxford paper got things wrong. “Averaging over technologies … gives [results] that may appear practically irrelevant,” the Spanish researchers wrote, which “misled Orben et al. (2019) to their conclusion that technology has no relevant association with well-being, whereas we argue that 1.88 higher odds of thinking about suicide are definitely practically relevant.”

Using the same advanced statistical technique as the Oxford researchers, my colleagues and I found substantial links between social media use and mental health, especially for girls.

That makes three independent research groups who all found significant links between social media and mental health in the same datasets the Oxford researchers dismissed as inconsequential.

Why were the Oxford researchers’ results so different? As the Spanish researchers document, the Oxford researchers were right that there was only a small link between social media use and mental health when mental health was assessed by the teens’ parents. There was a much bigger link when teens reported on their own mental health – suggesting that parents weren’t aware how much teens were actually suffering.

That had a big impact on the results, because the Oxford researchers included the one parent-report scale 8 times, including the total scale, 5 subscales, and 2 combinations of scales, while counting each of the 3 teen-report scales just once. Via this strange choice, the parent scales were 73% of their data (8 out of 11). (There are more details about that paper here).

There’s also a disconnect across fields. Research psychologists often dismiss correlations of .10 or .20 as “small,” even though those correlations can mean that twice as many heavy users of social media are depressed compared to light users. Correlations around .10 can definitely be impactful; for example, the correlation between childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is -.11. Researchers publishing in medical and public health journals are more likely to compare rates of depression across levels of use, leading them to conclude that there are substantial links. Psychologists are slowly changing their thinking on this, though, acknowledging that effects once dismissed as small are actually very common in the field and can have a big effect on certain people or can cumulate over time.

And: The links between social media and depression among individuals are only a part of the story. When social media became the norm among teens, a catch-22 was created: Use social media and be subject to all of its stresses, or don’t use it and feel left out. Because the way teens socialized changed so fundamentally (for example, they also weren’t seeing each other in person as much, even teens who didn’t use social media were affected. These group-level effects are likely a big reason why teen depression increased so much, even beyond effects on individuals.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.