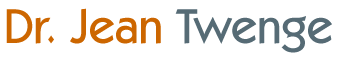

There’s rough consensus around these birth year cutoffs for the four most recent American generations:

Baby Boomers: 1946-1964

GenX: 1965-1979

Millennials: 1980-1994

GenZ/iGen: 1995-2012?

Of course, any birth year cutoff is arbitrary. (I’ve written more about that HERE and HERE). For example, maybe Millennials begin in 1979 or 1982 instead. That’s certainly possible – there is no bright dividing line between GenX’ers and Millennials. There are more definite breaks in the data between those born in the early 1990s and the mid-1990s, probably due to the smartphone, so the 1995 cutoff has some data to back it up. 2012 is looking fairly good for the last birth year of GenZ. Those born before 2012 will remember the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns for the rest of their lives. But those born in 2013 or later, who were 7 or younger in 2020, are less likely to have fully processed just how much our lives changed during this time. Since the pandemic was a major cultural event, 2012 seems to work as a birth year cutoff. Then we’ll be on to the next generation. We’re not sure what they will be called yet, though the term Alphas seems to be winning.

Generations exist because cultures change. Just as Japan has a different culture from the U.S., the culture of the 1950s was different from the culture of the 2020s. As cultures change, younger people – who have never known another world – take certain attitudes and worldviews for granted. These specific changes often stem from broad, pervasive forces in the culture.

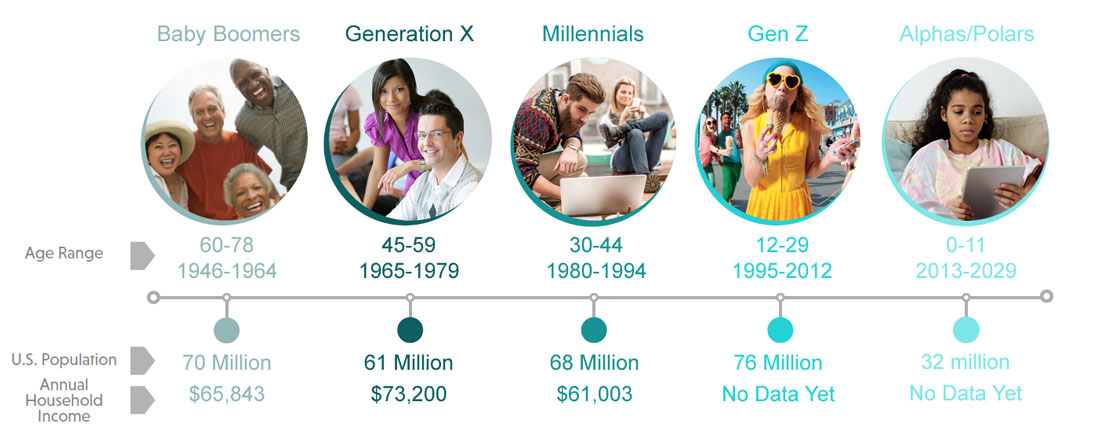

Traditional theories of generational differences argue that the major events experienced by each generation shape their worldview. However, major events are only a small part of the picture of why (for example) it was so different to grow up in past decades compared to now.

The most impactful force has instead been changes in technology. A hundred years ago, women (and it was always women) had to spend all day doing laundry; the introduction of automatic washing machines changed that. Teens used to socialize in person, but after smartphones and social media became more common, socializing moved mostly online.

Technology also changes cultures via secondary forces, including increasing individualism (more focus on the self and less on others) and a slower life (taking longer to grow up and longer to grow old). In Generations, I model the causes of generational differences like this:

Here’s just one example of technology’s downstream impact. Advances in medical technology have meant longer lives. In 1940, life expectancy was just 63. Even with COVID around, life expectancy was 77 in 2021. Technology has also led to a more complex society requiring more years of education. For both of these reasons, the entire developmental trajectory has slowed. Adolescents take longer to do adult things (like drive, have a job, or date), young adults take longer to get married and have children, and older adults enjoy more years of life (“60 is the new 50.”) These major generational differences in the speed of the life cycle aren’t due to major events; they are due to the downstream effects of technology.

It’s easy to make a list of the major events each generation experienced. Boomers, for example, were young during the Vietnam War, and Gen Z grew up after 9/11. But listing major events doesn’t tell you much about how the generations differ in their personality traits, attitudes, and behaviors. That’s the approach I take, analyzing nationally representative survey data on 39 million people.

For example, my book Generations relies on 24 nationally representative surveys. Most include data across several decades. That’s powerful, because they allow us to compare the generations at the same age. That means we can know what is really different across the generations apart from being a certain age.

Here are examples of some of the datasets I have worked with:

Monitoring the Future, 1976-present

General Social Survey, 1972-present

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2000-present

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, 1984-present

Most of these datasets don’t yield their secrets easily. Finding the generational trends involves downloading the datasets, merging the files, recoding variables, and running analyses. I’m often asked why the dataset webpages don’t show the trends I document. Most often, it’s because it takes so much time to merge the datasets and do the analyses. That’s what I have spent my career doing. (And making graphs. Generations has 282 graphs!)

Around 2012, I started to see some sudden changes in the big national surveys – depressive symptoms and loneliness started to go up, and (after going up for 20 years) happiness started to go down. Other sources – like national screening studies on depression and statistics on teen suicides – showed the same pattern, with increases after 2010-12. I wondered what was going on, so I thought about what might possibly have caused these shifts. The Great Recession was officially over by 2010, and unemployment started to fall around 2011, so it seemed unlikely that the economy was to blame. This period didn’t see any cataclysmic events – and certainly none that kept accelerating over the next five years.

Then three things happened, and the puzzle pieces began to fall into place. First, the Pew Center’s data showed that the percentage of Americans owning a smartphone crossed 50% at the end of 2012. Second, I found that social media moved from optional to mandatory among teens in 2010 . Third, I and many others found that young people who spent more time on social media were less happy and more depressed. So this was a suspicious pattern: A sudden rise in mental health issues when smartphones and social media became ubiquitous, and a link between social media use and mental health issues. For more on this, see the excerpt of iGen in The Atlantic. Overall, GenZ is a less confident, more uncertain, more anxious generation than Millennials were at the same age. That may at least partially be due to their adolescence spent on their smartphones.

Since iGen was published, more studies have documented troubling trends in teen and young adult mental health in the U.S. since 2010, including increases in self-harm behaviors , suicide attempts by poisoning, hospital admissions for suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, and suicides. Many of these increases are more pronounced among girls. Similar increases appear in the U.K. and in Canada. Jon Haidt (author of The Coddling of the American Mind) and I have reviewed the evidence for increases in adolescent mental health issues in a Google doc.

When teen depression started to increase in the U.S. survey datasets in 2012, I had no idea why. At first, I thought it might be a blip. Then depression kept rising with each year, into 2013, 2014, and then 2015. At that point it seemed imperative to figure out the cause.

Poor economic conditions were easy to eliminate: Unemployment was going down at this time as the U.S. economy finally improved after the Great Recession. Increases in income inequality had leveled off after rising the most between 1980 and 2000. So the increase in teen depression was a mystery.

Then, sometime in 2016, I found a Pew poll: The end of 2012 to the beginning of 2013 was the first time the majority of Americans owned a smartphone. It was also around the time teens’ social media use moved from optional (with about 50% of teens using it daily) to almost mandatory (80%+ of teens using it daily). Then the datasets yielded further secrets: Teens were also spending less time with their friends in person and sleeping less. In other words, the way teens spent their time outside of school had fundamentally changed. It would be surprising if that didn’t have an impact on mental health. That was the argument I made in iGen in 2017, and found further support for in Generations.

So how do we know that something else didn’t cause the increase in teen mental health issues? Let’s break down the alternatives and see if they fit the data.

A. Teens are more depressed because of the COVID pandemic. Given that teen depression had already doubled by 2019, the COVID pandemic (which did not impact the U.S. until March 2020) is clearly not the original cause. Depression kept increasing after 2019, but at about the same pace as it did 2012-2019.

B. Teens became more likely to self-report symptoms of depression due to lessened stigma or some other factor. If this explained the increase, you’d expect no changes in behaviors linked to depression, since behaviors aren’t self-reported. However, there have been large changes in behaviors: Self-harm, suicide attempts, and suicides all rose among teens at the same time self-reports of symptoms rose. We’ve known about the concurrent increases in behaviors since at least 2017, but this argument is still made despite the strong evidence against it.

C. Worries around climate change caused the increase. If that were true, we’d expect the increase in teen depression to be steady since at least the late 1980s or early 1990s when the issue gained major prominence (TIME magazine made “Endangered Earth” the Planet of the Year in 1989”. Or perhaps it would start in 2006 when Al Gore’s documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” was widely discussed. But neither was true: Depressive symptoms among teens were fairly steady 1991-2011, and teen suicide rates declined 1994-~2010. Plus, if climate change worries were the cause, you’d expect the largest increases among older teens, who are more aware of global issues. Instead, the largest increases in depression, self-harm, and suicide are among 10- to 14-year-olds. And if anxiety around climate change was the primary driver, why would teen loneliness also increase? It’s difficult to explain why climate change worries would cause loneliness, but easy to explain why spending more time online and less time with friends in person would cause loneliness.

D. Worries about school shootings caused the increase. If that were true, we’d expect the increases to begin in the mid-1990s when school shootings first attracted major news coverage, especially Columbine in 1999. Again, though, that’s not when the increases started. Plus, if school shootings were the cause, teen depression would not increase in countries with much lower rates of gun violence than the U.S. But depression does rise elsewhere, including in the UK, Canada, and Norway. In addition, teen loneliness increased 2012-2018 in 36 countries around the world.

E. Teens have more homework and are under more academic pressure than in previous eras. Actually, teens don’t have more homework (they have less) and don’t report more academic pressure.

F. More marijuana use among teens caused the increase. Except marijuana use among teens was stable to declining at the same time teen depression was rising after 2012. The declines were largest among the youngest teens, the population with the biggest increases in depression and self-harm.

In my view, the question is this: What, other than new technology, had such a big impact on teens’ lives between 2012 and 2019?

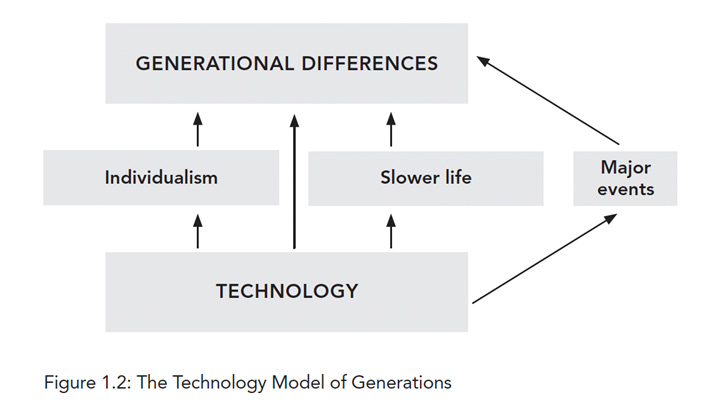

Several researchers have tried to make this case, often relying on studies with poor measures of social media use, such as those asking if someone uses social media every day – nearly everyone who uses social media now uses it every day. We also know from studies with better measures (like those asking about hours a day of social media use) that it’s social media use of hours and hours a day that’s linked to depression, not use under an hour a day.

The paper most often cited to support this idea of small effects, published in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour by researchers from Oxford University, actually examined screen time overall, not social media specifically. It included watching TV, talking on the phone, and simply owning a computer as screen time, which obscured the results for social media. The same month this paper was published, another research group in the UK found that girls who spent 5 or more hours a day on social media were three times more likely to be depressed than those who did not use social media – in one of the same datasets the Oxford researchers used (see below).

In 2022, a group of Spanish researchers also concluded that the Oxford paper got things wrong. “Averaging over technologies … gives [results] that may appear practically irrelevant,” the Spanish researchers wrote, which “misled Orben et al. (2019) to their conclusion that technology has no relevant association with well-being, whereas we argue that 1.88 higher odds of thinking about suicide are definitely practically relevant.”

Using the same advanced statistical technique as the Oxford researchers, my colleagues and I found substantial links between social media use and mental health, especially for girls.

That makes three independent research groups who all found significant links between social media and mental health in the same datasets the Oxford researchers dismissed as inconsequential.

Why were the Oxford researchers’ results so different? As the Spanish researchers document, the Oxford researchers were right that there was only a small link between social media use and mental health when mental health was assessed by the teens’ parents. There was a much bigger link when teens reported on their own mental health – suggesting that parents weren’t aware how much teens were actually suffering.

That had a big impact on the results, because the Oxford researchers included the one parent-report scale 8 times, including the total scale, 5 subscales, and 2 combinations of scales, while counting each of the 3 teen-report scales just once. Via this strange choice, the parent scales were 73% of their data (8 out of 11). (There are more details about that paper here).

There’s also a disconnect across fields. Research psychologists often dismiss correlations of .10 or .20 as “small,” even though those correlations can mean that twice as many heavy users of social media are depressed compared to light users. Correlations around .10 can definitely be impactful; for example, the correlation between childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is -.11. Researchers publishing in medical and public health journals are more likely to compare rates of depression across levels of use, leading them to conclude that there are substantial links. Psychologists are slowly changing their thinking on this, though, acknowledging that effects once dismissed as small are actually very common in the field and can have a big effect on certain people or can cumulate over time.

And: The links between social media and depression among individuals are only a part of the story. When social media became the norm among teens, a catch-22 was created: Use social media and be subject to all of its stresses, or don’t use it and feel left out. Because the way teens socialized changed so fundamentally (for example, they also weren’t seeing each other in person as much, even teens who didn’t use social media were affected. These group-level effects are likely a big reason why teen depression increased so much, even beyond effects on individuals.

Large correlational studies are very consistent in finding that teens who are heavy users of social media are more likely to be depressed than light users. But does heavy social media use cause depression, or does depression cause heavy social media use?

The gold standard for answering this question is a random assignment experiment. For example, researchers could randomly assign some people use social media their normal amount (the control group) while others stop using social media or cut back on their use (the experimental group). Many studies have taken this approach (for a list of these studies, click here). When these experiments last two weeks or more, they nearly always find that those who cut back or eliminated social media use are happier and less depressed.

These studies are actually even stronger evidence than they might first appear – they ask average users to cut back to light or no use. In the correlational data, the largest differences are instead between average users and heavy users. If experiments asked heavy users to cut back their use for several weeks, effect sizes would likely be even higher.

One set of researchers took advantage of a natural experiment: Facebook rolled out at different times across college campuses. Sure enough, mental health issues rose among students when their campuses adopted Facebook.

There’s also the question of whether we’re considering individuals or groups. At the group level, when trying to explain why teen depression rose so much since 2012, it seems more clear that social media use (and/or the prevalence of smartphones) cause depression, and not the other way around. If depression caused social media and smartphone use, you’d have to argue that an unknown factor caused teen depression to increase, which then led teens to buy smartphones and start using social media more. That seems pretty unlikely – the technology came first and grew in popularity, and then teen depression rose.

With the oldest in their late 20s, Gen Z are now the vast majority of young hires. As the Boomers retire and businesses compete more and more for talent, understanding this generation has never been more important.

First, recognize that Gen Z are different from Millennials – less optimistic, more practical, and more interested in a job where they can help others. The same strategies that worked for Millennials are often not going to work for Gen Z.

If you’re interested in learning more about how you can use the data on generational differences to recruit, retain, and manage Millennials and Gen Z, click here.

Gen Z has a lot of strengths. They have a strong work ethic and a practical orientation toward work. They take equality based on race, gender, and sexual orientation for granted and are arguably the least prejudiced generation in history. They are also the safest — for example, fewer get in car accidents, and fewer binge drink. That’s not just because of their parents: Gen Z themselves are more concerned with safety and are less willing to take risks than previous generations.

Gen Z teens are much less likely than Gen X teens in the 1990s to smoke, drink alcohol, have sex, or get pregnant — so there’s been significant improvement in many of the things parents worry about. Some of this is rooted in protective parenting and safety concerns, and some in the decline in face-to-face social interaction among teens during the smartphone era. In general, Gen Z is taking longer to grow up than previous generations; as 18-year-olds, they are less likely to have a drivers’ license, work at a paid job, go out on dates, or drink alcohol than 18-year-olds were 10 or 20 years ago. Those are all things adults do and children don’t, so they have historically been milestones of adolescence. Some of these trends are positive, some are not — it’s more important to see the big picture of slowed development rather than focus on good or bad. So it’s not that Gen Z teens are more responsible (or less responsible), or more mature (or less mature), it’s that they are taking longer to grow up.

No, because it uses data from young people themselves. These studies compare young people’s views and behaviors to the views and behaviors of young people from previous generations. Of course, like any scientific study, these are average differences, so there are certainly exceptions. People from Minnesota (where I spent my childhood) are different from people from Texas (where I spent my adolescence), but there’s plenty of individual variation. Generations work the same way. There’s more on that here.

One other note: The trends reported in iGen are based on nationally representative samples, so they capture the experience of the typical teen. The generational trends are very consistent across race, gender, socioeconomic status, and region of the country, with just a few exceptions (for example, the mental health trends are larger among girls).

Maybe, but that observation isn’t particularly relevant for this data, which examines what young people say about themselves. I completely agree that older folks’ observations are not a useful source of data about generational differences. That’s why the studies rely on the voices of the generation itself. This question also seems to assume that an argument which has been made before must be wrong. That seems nonsensical at best. Instead, it makes sense to listen to what young people have to say, and to find out how that’s different from what they said 10, 20, or 30 years ago.

Related to this is “people have always worried about the effects of new technology – they said the same thing about novels, TV, etc.” Again, just because it’s been said before doesn’t make it wrong. For example, people were probably right to worry about TV: It’s also correlated with depression, and political scientist Robert Putnam concluded in his book Bowling Alone that TV was the primary reason community groups and social capital declined after 1950.

As for novels, we don’t have data to determine if they had negative effects when they were introduced. But among today’s teens, those who read books, magazines, and newspapers are happier than those who don’t. Thus, this observation isn’t particularly relevant to today’s teens.

Millennials have been shaped by the growth of cultural individualism – more focus on the self and less on social rules. Individualism explains nearly all of the Millennial generation’s distinguishing characteristics, from their support of equality to their positive self-views. Millennials are also focused on standing out, feeling unique, and having high expectations for themselves. With iGen less confident, Millennials represent the apex of the individualistic idea that you should always feel good about yourself. iGen has continued individualistic trends toward supporting equality, with iGen and the Millennials really standing out from previous generations in their support for LGBT issues.